GERIATRIC DEMENTIA

INTRODUCTION

While any serious medical condition can challenge both caregivers and medical professionals, disorders that cause dementia, cognitive impairment, and disruptive behaviors can be particularly challenging. Proper approaches to assessment and therapy continue to challenge the clinician, and dealing with the demented loved one can become the ultimate emotional challenge and very demanding of caregivers’ time and patience.

Noncognitive disruptive behaviors such as agitation, nighttime restlessness, disruptive vocalizations, psychotic symptoms, and physical aggression tend to cause more trouble to caregivers than the dementia itself and frequently lead to premature institutionalization. These symptoms, which affect around 80% of demented patients at one time or another, add greatly to the burden of caregivers as well as the health care system. The patient with cognitive impairment accompanied by disruptive behaviors is substantially more disabled than one with only cognitive impairment and may decline functionally at a greater rate. Various therapies have been utilized over the years to increase patients’ comfort and improve ease of care, independent of cognitive impairment? These therapies have ranged from anxiolytics, antidepressants, and mood stabilizers, to antipsychotics and cholinomimetics, as will be discussed later.

CAUSES

Possible causes of dementia and associated disruptive behaviors are numerous (see Table 1), and none are so thoroughly studied or as prevalent as Alzheimer’s disease (AD). AD accounts for approximately two thirds of all dementia cases; and most of the rest, regardless of the primary cause, bear considerable resemblance to Alzheimers with regard to symptoms, including disruptive behaviors.2

AD’s most significant risk factor is advancing age. Four million Americans are currently affected, but with the percentage of the US population over age 65 growing rapidly, dementia and its associated disruptive behaviors loom like a threat on our demographic horizon.15

The high treatment costs associated with escalating numbers of AD victims could be devastating to the health care system, to say nothing of the Human costs, both for the victims themselves and for their families, who must provide daily care and emotional support while watching the inevitable decline of loved ones. With these facts in mind, this discussion will focus on AD as the primary cause of dementia in elderly patients. In any case, any underlying cause(s) for dementia and/or associated psychotic or agitated symptoms must be recognized and properly addressed.1

DEMENTIA AND DISRUPTIVE

BEHAVIORS

At least some form of dementia affects an estimated 10% to 15% of the population over the age of 65 and 50% of those over 85. Dementia is typically a progressive inability to reason and correctly assess the environment (cognitive impairment), causing increasing disorientation and confusion, deteriorating memory, judgment, and personality, and increasing impulsive behavior.

Table 1. Possible Causes of Dementia

Degenerative Dementias Vascular Dementias Anoxic Dementia

Alzheimer's Disease Multi-infarct dementia Trauma or infection

Pick's Disease Cortical micro-infarct Toxicity (alcohol, metals

Huntington's Disease Lacunar large-infarct poisons, polypharmacy)

Progressive supranuclear Binswanger's disease Space-occupying lesions

palsy Cerebral embolic disease Autoimmune disease

Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis Multiple sclerosis Vasculitis

Parkinson-ALS dementia Disseminated lupus (SLE)

Genetic & metabolic diseases

Disruptive behaviors are common to most mental disorders that could be confused for dementia, including retardation, personality disorder, schizophrenia, depression, and simple age-related memory loss? They are also common in acute confusional state, or delirium, which frequently complicates medical illness in the older patient. Sudden onset of cognitive dysfunction or noncognitive disruptive behaviors in older patients must be investigated with this in mind, evaluating for common precipitants like urinary or respiratory infection, dehydration, poor nutrition, pain, or even insomnia or constipation.

Assessment can be complicated by polypharmacy, sensory impairment (difficulty in hearing or seeing), and psychosocial stresses—all situations commonly affecting the elderly, especially in the long-term care environment, where effective patient communication may also be significantly impaired in the absence of dementia.

Dementia, therefore, must be more narrowly defined to include not only loss of memory but also impairment in at least one other cognitive function (see Table 2).

It comprises a syndrome that impairs daily function and is usually chronic, progressive, and rarely reversible. Diagnosis of dementia is beyond the scope of this article, because it requires neurological assessment, direct observation of behavior, interview of a caregiver, full medical history, and formal cognitive function testing?

Disruptive behaviors are common with dementia. They are often the primary reason for institutionalization, proving too difficult and demanding for loved ones. Proper care of demented patients requires caregivers who are not only devoted but also well-rested and cared-for themselves. The caregiver relentlessly stressed by a demanding or abusive loved one incapable of routine self care may soon become another patient to be treated.

Demented patients with disruptive behaviors are thus concentrated in long-term care facilities. Various studies have looked at the prevalence in these facilities of mental disorders with primary diagnoses of dementia and at least one behavioral problem. They have reported an incidence as high as 90% -- with 50% of affected patients showing four or more disruptive behaviors.

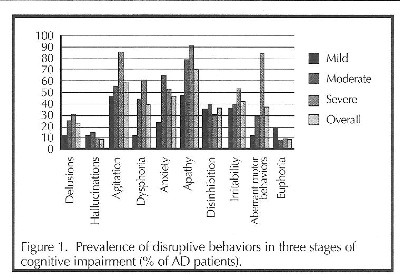

Delusions, hallucinations, agitation, dysphoria, apathy, anxiety, disinhibition, irritability, aberrant motor behavior, and euphoria are noncognitive behaviors all common in dementia. These behaviors may increase or decrease in frequency and severity as dementia progresses (see Figure 1).5

The following are brief descriptions of common disruptive behaviors associated with dementia.

Delusions (false beliefs) may be nonproblematic, with the patient believing he lives in another time or place with departed loved ones or imagined cohabitants. These delusions may even be comforting to the patient and require no treatment.

However, paranoid delusions are a common source of anxiety and agitation when the patient becomes preoccupied with dangers from real but unrecognized loved ones and caregivers, or from imagined perpetrators. interestingly, delusions tend to be more prevalent as dementia becomes more severe, while hallucinations are more common among moderately demented patients.6 Hallacmattons are perceived unreal visual or auditory stimuli.

Agitation, the most common disruptive behavior in AD, is a broad category that includes physical or verbal aggression, noncompliance (refusal to cooperate), obstinacy, and crying. It is observed in about 85% of AD patients and is the most common cause of institutionalization. Agitation, like delusions, tends to worsen as dementia progresses.6 It may be perceived as a personality change in early stages, where the patient becomes uncharacteristically stubborn or worried. As dementia progresses, agitation requires more frequent reassurance, supervision, and intervention.7

Dysphoria (disquiet, restlessness, malaise) follows a similar trend of high prevalence in severe dementia and is relatively rare in mild impairment. It is distinct from depression, which is feelings of unhappiness. Dysphoria and depression share common features according to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-IV) and tend to overlap, especially in the area of apathy (absence of feeling or emotion),5 which is also very common in AD and more common in severe impairment. Dementia itself is also noted for causing a variety of symptoms seen in major depression, including anhedonia, weight loss, insomnia, and agitation, so AD patients are also often diagnosed as clinically depressed.

Anxiety is often included in a broader definition of motor restlessness, but it is more accurately described as worried, frightened, tense, or fidgety behaviors with no apparent reason. Like hallucinations, anxiety tends to be most common among patients with moderate cognitive impairment and less common among the

severely impaired. It is as if worsening cognition increases anxiety until the point where ting) impairment actually helps diminish anxiety.

Disinhibition can lead to inappropriate behaviors or responses, including sexual disrobing in public, aggression, and violence. It is seen in about 50% of AD patients, but it can be extremely difficult to manage and traumatic for caregivers. Disinhibition is more common in moderate cognitive impairment than in mild or severe dementia.7

Irritability is slightly different from agitation, defined as rapid emotional fluctuations between frustration and impatience. Though slightly less common than agitation, irritability also increases in prevalence as dementia progresses.

Aberrant motor behaviors like pacing, searching,

rummaging, or picking at one’s clothes are as common as agitation in the severely demented. However, such behaviors are unusual in mild cognitive impairment, so when they occur, delirium with underlying medical pathology may be suspected as an important contributing factor.6

Euphoria, feelings of elation in excess of what circumstances warrant, is relatively rare compared to other disruptive behaviors. It seen in less than 20% of mildly demented patients, almost never in those with moderate impairment, and in less than 10% of those with severe dementia. It also tends to be less problematic than other disruptive behaviors when it does occur, but may still require management in some cases.

It is important to note that in the study from which the above data was taken,8 some patients with only mild cognitive impairment suffered multiple severe disruptive behaviors, while others who were severely impaired suffered few or very mild disruptive behaviors. These behaviors also tended to be erratic in occurrence, seemingly exacerbated or ameliorated spontaneously, in many cases independently of cognitive impairment.

Perhaps the most important consideration in discussing disruptive behaviors is their relationship to functional capacity. Cognitive impairment certainly reduces the ability to cope with personal care-taking, ranging from an inability to maintain one’s stock portfolio to the failure to recognize when it’s time to find the bathroom. The popular notion has prevailed that disruptive behaviors substantially add to the functional deficits seen with dementia, that the demented patient with disruptive behaviors is significantly more impaired

regarding functional status than the AD patient without such behaviors.8 One study, though, refutes this belief, showing no such connection. In this study, cognitive impairment was the most significant factor in functional disability, while disruptive behaviors did not contribute significantly. The conclusion drawn by the authors was that the additional functional impairment seen in patients with disruptive behaviors in other studies may well be caused by medications used to control such behaviors.9

MEASUREMENT OF DISRUPTIVE BEHAVIOR

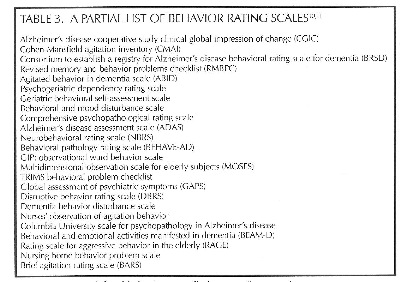

Any examination of such behaviors, their impact on patients or society, or their relationship to medication, cognitive impairment, or other factors is complicated by the fact that there is no uniform standard by which these parameters can be reliably measured. It is therefore difficult, at best, to quantify such behaviors in any setting. Numerous attempts have been made and study outcomes published (see Table 5) to establish such standards, and many have been utilized in clinical studies, all with inherent liabilities that render their findings questionable.10,11

When examining incidence, prevalence, and severity of such behavior -- not to mention the effects of any pharmacological or nonpharmacological treatments used -- the variables can be overwhelming. It would be all but impossible to amass a group of patients standardized for age; cause, severity, and duration of dementia; prior

treatments for dementia, duration of institutionalization, and comorbidities and their treatments.10,11

Even if such a homogeneous group were possible, measuring behaviors is far from an exact science; it must rely on observation and evaluation of the patient’s behavior by a third party whose perception or judgment may vary from day to day.

Various studies have used nursing facility staff, spouses or other homebound caregivers, nursing supervisors, physicians, psychiatrists, and trained observers. Any method that requires evaluation by care facility staff is suspect, since it is typically the staff’s job to maintain order, avoid disruption, and make the lives of everyone in the facility easier by discovering and avoiding triggers to disruptive behaviors. This may be one factor in the observation that frequency of disruptive episodes tends to decrease over a period of weeks, even without formal intervention.10,11

TABLE 2. AREAS OE COGNITIVE FUNCTION OTHER

THAN MEMORY LOSS

• Attention

• Orientation

• Communication (ability to speak or write or to comprehend speech or writing)

• Recognition of people or objects

• Abstract thinking (ability to use and understand proverbs and metaphors)

Most measurement tools rely on reports on the number as well as severity of incidents that demonstrate defined behaviors, usually by way of a numerical score. This methodology has a variety of statistical problems and leaves many difficult questions to be answered. Should symptoms be rated from O to 6, from 1 to 7, or + to ++++? What is the cut-off score below which a symptom is considered insignificant or resolved? How are rules devised to differentiate symptoms with overlapping components like apathy, depression, and withdrawal? What is the difference between verbal assaults classified as aggression as opposed to irritability? The overwhelming nature of the problem is illustrated by the number and diversity of rating scales used in various clinical trials.10,11

TRIGGERS AND NONPHARMACOLOGIC

STRATEGIES FOR MANAGEMENT OE

DISRUPTIVE BEHAVIORS

One of the most significant factors in optimizing the care of patients with impaired cognitive function, with or without disturbing behaviors, is education of caregivers in providing the right environment for such patients. The long-term care environment has traditionally been oriented toward the economical care of affected individuals, with the convenience of the staff taking precedence over actual patient welfare

In the past, disruptive behaviors were managed by medication in order to make the job of dealing with such patients less problematic and less expensive for the institution. Many such behaviors, though, can be avoided or at least minimized by recognizing and reducing the impact of possible triggers. Arming caregivers vvith proper training in behavior management is essential.3,7

While many such behaviors seem spontaneous and random, agitation and aggression, for instance, may often be understandable responses to the demented patient’s perception of and confusion by disorienting factors in his environment. With disinhibition and irritability, the patient’s normal response to simple stresses like perception of losing control, being subordinate, or being unable to cope with a simple task may become exaggerated and produce a violent response.

A prime example of this is "sundowning,” where an otherwise docile AD patient becomes agitated and irritable at dusk or at lights-out because of the light change. This patient, who suddenly begins to pace or fidget or becomes aggressive with caregivers, may simply feel threatened by the disorienting change. Acquiescing to such a patient’s internal schedule, maintaining a regular schedule, allowing him to pace, or increasing lighting may reduce his confusion and his aggressive behavior without medication.*

Agitation can result from a host of disorienting or uncomfortable stimuli with which the demented patient finds himself unable to cope and about which he is unable to communicate. Disorientation can be a function of inadequate lighting or disruption of expected schedule. Physical pain, or simple discomfort from constipation or needing to go to the restroom and/or frustration from inability to recognize or communicate those facts, can cause aggression. Confusion can result from too much activity, too many people, too much noise, or inability to understand a simple request.7

Levels of irritability, agitation, and anxiety and incidents of aggression may be reduced in many patients simply by adhering to a regular schedule or by reducing distractions by providing a quiet, calm, and familiar atmosphere. Making time for pleasant accustomed activities like sharing a walk, playing simple card games, or watching favorite television programs can also help allay such symptoms, as can redirecting the disruptive patient with simple repetitive tasks or the rummaging patient with a sorting task.7

Keeping tasks simple can reduce frustration over an inability to handle tasks that were once easily managed. That can be done by breaking down more complex tasks like dressing or bathing into smaller, more manageable segments. Soothing activities like brushing the hair or getting a massage or a manicure can be calming and redirecting. Simply remaining flexible to accommodate the patient who is sundowning by allowing activity after dark instead of insisting on an imposed sleep cycle can help. Tolerating wandering or pacing activity, reducing the chance for injury during activities, and providing a familiar place to indulge them can often help reduce confusion, agitation, and anxiety. Sometimes even very strange behaviors might be better tolerated than medicated, especially if they help keep the patient calm and are confined to the privacy of one’s private residence7

PHARMACOTHERAPY

Obviously, difficult behaviors are not always amenable to such measures. They may become intolerable or unmanageable, either temporarily or progressively. Nonetheless, nonpharmacologic measures discussed above are always an appropriate first-line approach, and they remain appropriate adjuncts to more aggressive medical therapy.

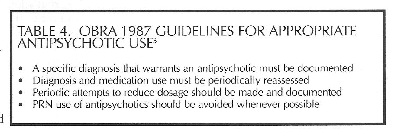

To combat the disturbing trend toward chemical restraint, where anyone exhibiting disturbing behaviors was automatically sedated in times past simply to facilitate patient management, OBRA 1987 provided official guidelines for appropriate use of antipsychotics (see Table 4).5

Pharmacotherapy is aimed at symptom control, so determining an appropriate psychobehavioral metaphor is the first step in choosing appropriate therapy. Psychobehavioral metaphor is a complicated name for the only slightly less complicated process of deciding to which major medicationresponsive category most displayed symptoms belong. Since symptoms tend to occur in clusters and overlap considerably, careful distinctions may be necessary in arriving at the most appropriate metaphor. For instance, the agitated and negativistic patient with severe irritability may be most appropriately treated with trazodone; the restless, stressed, apprehensive patient without paranoia may respond better to an anxiolytic agent; and the hyperactive and aggressive insomniac with pressured speech may be more appropriately treated with a mood

stabilizer.3

Psychotic symptoms like delusion, hallucination, or even delirium may respond best to antipsychotic agents; there is a definite trend toward atypical antipsychotics to avoid the problems inherent with tricyclic agents in elderly patients. Aggression and anger may respond best either to an antipsychotic agent or to agents that have come to be known as mood stabilizers in this role. These include the anticonvulsants divalproex and carbamazepine, or lithium carbonate. Insomnia may be treated with trazodone or even short-term benzodiazepines, which have their own liabilities in the elderly patient. Sundowning often responds well to trazodone or one of the antipsychotic agents. Anxiety may be best addressed long term with buspirone, with its favorable side effect profile, rather than short-term benzodiazepines. Depression is treated preferentially with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, with their favorable response rate and relatively benign side effects in most elderly patients, as opposed to the tricyclic agents. When chronic pain must be treated, the tricyclic agents may be the best option in appropriate patients.7

THE MEDICATIONS

Cholinomimetics

Cognitive skills of language, visuospatial abilities, and memory deteriorate perpetually and linearly in the AD patient, while disruptive behaviors tend to occur episodically throughout the course of AD. That would seemingly lead to the conclusion that disruptive behaviors and the deterioration of cognitive skills are due to separate pathologies. It stands to reason, though, that

efforts to improve cognitive symptoms and delay cognitive decline may also improve or delay behavioral symptoms, though this theory is only applicable when AD is a primary factor in dementia.

Cognitive decline in AD is attributed to cholinergic deficiency in various areas of the brain (though changes in norepinephrine, serotonin, somatostatin, corticotropin releasing factor, and acetylcholine are all involved to some degree)12 these are metabolic changes that could cause or at least contribute to the multiple neuropsychiatric symptoms described as disruptive behaviors.

Adrenergic and serotonergic systems are undeniably interrelated with cholinergic systems, and the progressive cholinergic decline in AD must necessarily affect balance with the other systems, which can obviously affect behavioral symptoms,13

Thus, treatment of cognitive symptoms with cholinergic agents, though only a temporary means of delaying cognitive decline in the AD patient, often provides some relief of behavioral symptoms as well. Whether this effect is due to direct neurotransmitter changes or delay or improvement of cognitive decline underlying the other behaviors remains to be determined. When AD is the primary causative factor in dementia, the cholinergic agents may be a logical first-line pharmacotherapeutic choice in appropriate patients, especially early in the disease process.13

Tacrine -- The first of the reversible cholinesterase inhibitors, tacrine is approved for use in AD to treat mild to moderate dementia. It generally requires substantial doses (up to 160 mg per day titrated gradually upward from 40 mg per day) and frequent dosing (four times daily). Liver function is affected in about 40% of patients, with significant elevation in serum transaminase levels that may require discontinuation of the drug.

Tacrine is metabolized by the cytochrome P450 1A2 system, which causes a number of important drug interactions, most notably a significant increase in elimination time of theophylline and cimetidine. Interestingly, steady-state blood levels of tacrine tend to be about 50% higher in women than men, and indiscriminate cholinergic side effects like nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, sweating, and bradycardia, among others, necessitate cessation of therapy in almost 20% of patients.

In spite of its liabilities, tacrine has demonstrated improvements in apathy, anxiety, hallucinations, disinhibition, and aberrant motor behavior that are significant enough to delay institutionalization.13

Donepezil -- Donepezil bears the same indication as tacrine, but has a half-life of around 70 hours, which allows once-daily dosing at 5 mg to 10 mg per day. In addition, donepezil’s more specific inhibition of acetylcholinesterase gives it fewer and less severe side effects than tacrine. Cholinergic side effects are still not uncommon, but usually much less severe than with tacrine. Liver function is not significantly affected by

donepezil.13

Donepezil is metabolized by cytochrome P450 SA4 and ZD6 enzyme systems; while inducers and inhibitors of those systems may affect elimination of donepezil, it has little effect on the levels or clinical effects of furosemide, warfarin, digoxin, theophylline, or cimetidine.12 Its efficacy in temporarily improving cognitive function and delaying impairment is comparable to that of tacrine; similar effects are seen with respect to disruptive behaviors as well13

Rivastigmine -- Also FDA-approved for mild to moderate dementia in AD, rivastigmine is comparable in almost all aspects to the other two agents, with a side effect profile more closely resembling that of donepezil in severity. Like the others, it requires initiation of therapy at low doses with gradual upward titration toward optimum doses of 6 mg to 12 mg per day in order to minimize cholinergic side effects.

Metabolism of rivastigmine is also more similar to that of donepezil, primarily via cholinesterase-mediated hydrolysis to the decarbamylated metabolite. With minimal involvement of the cytochrome P450 enzyme systems, rivastigmine has shown no significant interactions involving other agents that utilize these systems. The agent is also available in an oral solution of 2 mg/mL, which may facilitate administration to demented patients.12

Galantamine - The acetylcholinesterase inhibitor most recently approved by the FDA for the same indication, galantamine, works similarly to the agents above. While initial studies show a relatively favorable cholinergic side effect profile, comparative studies are limited. The 4, 8, and 12mg tablets are designed for twice daily dosing, with the recommendation for initiation of therapy at 8 mg/ day and titrating upward at intervals of at least 4 weeks to minimize cholinergic side effects. Metabolism via the cytochrome P450 systems is similar to that of tacrine and donepezil, with no hepatotoxicity seen in clinical studies.12

These acetylcholinesterase inhibitors increase synaptic acetylcholine by inhibiting its destruction; though they may produce marked improvement in both cognitive and neuropsychiatric symptoms in many patients, they may be of little value in others. As AD progresses, these agents tend to lose their efficacy, presumably due to progressive neuronal damage observed in AD, and a dramatic exacerbation of symptoms is not unusual upon discontinuation. All of these agents are limited by cholinergic side effects, so increasing dosage to counter escalating neural damage is not a viable option.13

Though seizure activity can be a function of AD pathology, cholinomimetics may tend to increase likelihood of seizure. Cholinergic side effects are common, including nausea, vomiting, diarrhea (largely associated with increased gastric secretion), increased sweating and salivation, vagotonic effects that can exacerbate bronchospasm and cause bradycardia and syncope; exaggerated succinylcholine-like muscle relaxation during anesthesia, and impaired bladder outflow.12

Though improvement of disruptive behaviors cannot be considered a primary reason to undertake cholinomimetic therapy, it may improve such symptoms as a byproduct of better cognitive function in appropriate AD patients. Improvement can only be expected in the AD patient, so such therapy is generally inappropriate in other types of dementia. Improvement is generally short-lived, typically masking and delaying characteristic symptomatology that worsens upon discontinuation.12

Typical Antipsychotics

The traditional antipsychotics (eg, phenothiazines, haloperidol, loxapine) have long been a target of concern, not only for their past history of widespread misuse as chemical restraints, but also because of questionable efficacy and side effects that can be particularly problematic in the elderly patient. These agents are generally very sedating, which can be an asset in treating acute violent episodes, but use without documented appropriate diagnosis is discouraged.

Other agents may be more appropriate in this application, since typical antipsychotics tend to diminish quality of life in many older patients. They can cause sedation and orthostatic hypotension (diminished baroreceptor sensitivity and venous tone in the elderly)14 which can increase the tendency to fall. They can also cause anticholinergic side effects like dry mouth that can lead to dental problems; poor appetite that can lead to malnutrition, constipation, and visual problems; impaired cognition and memory; lowered seizure threshold; extrapyramidal symptoms (EPS); and tardive dyskinesia (TD).15

Studies of the efficacy of typical antipsychotics in elderly populations have shown beneficial effects in only about 20% of patients. In one study, TD was seen in 31% of patients over the age of 55 who were taking antipsychotics, with no significant differences between the phenothiazines and haloperidol. Thus, when antipsychotic agents are indicated, it makes sense to check side effect profiles in choosing an appropriate agent.

Atypical Antipsychotics

Though there are few studies evaluating the efficacy of the atypical antipsychotic agents in elderly demented patients, evidence is good that a number of these agents can be more effective than the typical agents and with significantly fewer side effects.16

Risperidone - This drug has been studied in this role and has improved disruptive behaviors by about 50% (improved BEHAVE-AD scores) in 45% of patients on 1 mg per day and 50% of patients on 2 mg per day after 12 weeks of therapy. These results suggest that risperidone is effective in treating psychosis in this target population in doses of 1.0 to 2.0 mg per day for psychosis and in doses of 0.5 to 2.0 mg per day for behavioral symptoms, although this must be confirmed by further studies.16

Comparing risperidone, haloperidol, and placebo in the same applications, significant reductions in aggression were seen in patients taking risperidone compared with placebo, and EPS was seen significantly more often in patients taking haloperidol.16 EPS with risperidone is dose-related with incidence similar to placebo in doses of 1 mg per day, but about 50% of patients with dementia develop new or worsening EPS while on risperidone.17 Predictors of EPS include longer duration of therapy (6 months or longer), younger age, and concurrent antidepressant use. Risperidone metabolism involves cytochrome P450 ZD6, but other agents metabolized by other P450 isozymes are only weak inhibitors of risperidone metabolism.

Quetiapine -- This drug may also prove valuable in treating aggression, agitation, delusions, and hallucinations in dementia, producing some clinical improvement, though clinical studies involving demented patients are minimal. EPS is much less likely with quetiapine than other antipsychotics, even risperidone and olanzapine, and even in high doses (up to 800 mg per day); orthostasis and sedation were the most noted side effects in clinical studies of AD patients.12

Olanzapine -- This drug has been studied in AD patients and has shown improvement in hallucinations, delusions, and agitation, with EPS and anticholinergic side effects no more prominent than placebo, in spite of anticholinergic effects anticipated by the agent’s pharmacology.17

Somnolence and some dizziness remained the major side effects with olanzapine in these elderly patients.3,16

Interestingly, after examining results comparing 5 mg, 10 mg, and 15 mg daily with placebo, the best long-term results in reducing disruptive behaviors were seen with the median dose. Though initial response was better with the 15 mg dose, the agent’s benefit seemed to plateau sooner than with the lower dose, which continued to improve symptoms over a longer period.18

Disruptive behaviors in the demented patient are often considered medical emergencies, in that the 5 patient may pose significant risk of injury to himself or

to those around him. Expert Consensus Guidelines now recommend olanzapine or risperidone in such situations from the standpoint of side effect profiles, particularly in the elderly patient. Typical agents, neuroleptics, or benzodiazepines previously more traditionally utilized in this role due to availability in injectable dosage forms, obviously have facilitated more rapid control of such symptoms and more efficacious defusing of the emergency situation. The higher rates of extrapyramidal symptoms, not to mention sedation and neurological predisposition to dystonia remain significant liabilities, and initiation of therapy with such agents may impede transition to oral atypical agents once deemed appropriate. Thus, the availability of olanzapine in an intramuscular dosage form, with proven efficacy and safety in rapidly controlling agitation in the demented patient has made it the logical first choice in many such situations.12

Clozapine -- This drug has been studied more in Parkinsons patients, so there are little data involving dementia. When studied in dementia, some patients showed improvement in delusions and agitation, while others show no benefit with clozapine.16 Given the relative severity of potential problems with using clozapine in elderly patients (most notably agranulocytosis), the recommendation remains that clozapine be tried only after other options have failed?

Consensus Statements

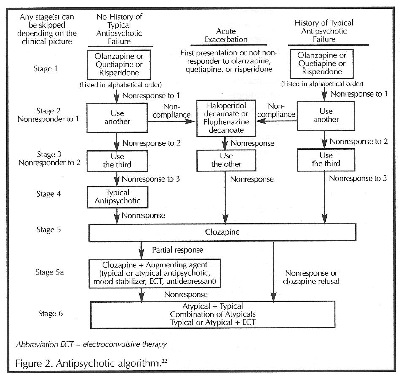

Current published consensus statements that continue to recommend typical antipsychotic agents are admittedly based on a dearth of clinical studies evaluating the atypical agents in comparison with typical agents or among themselves. Although preliminary data on the efficacy of atypical agents in dementia are beginning to surface, trials are ongoing. Until head-to-head trials are published, data are insufficient to make recommendations for a first-line agent.U In spite of the lack of data, a treatment algorithm has been devised for longterm treatment of psychosis using clinical expertise to "fill in the gaps."

(Figure 2).22

This algorithm is intended to be a "dynamic recommendation" subject to periodic updates and revisions pending new medications, post—treatment evidence, and research. Before changing agents, a sufficient trial period must be given to the initial choices to establish adequate doses. Especially in the elderly, initiation with low doses is recommended, with slow upward titration to maximum doses or intolerance before another agent is tried.16,17

Mood Stabilizers

Both carbamazepine and divozyaroex have been used as mood stabilizers to treat disruptive behaviors, especially aggression, impulsiveness, and friable affect; some studies indicate that up to 60% of demented patients can benefit from one of these agents. While carbamazepine is probably the most thoroughly studied agent in this class, divalproex is the only anticonvulsant agent with FDA approval for treatment of mood disorders. Mechanism of action in this application is only speculation, but must certainly involve balance between neurotransmitters.3,19 In clinical studies, as many as 77% of patients' disruptive behaviors improved on carbamazepine at a dose of 500 mg per day, but side effects were common. Another study found 54% of patients unresponsive to other therapies "improved or much improved" by divalproex in doses ranging from 375 mg to 1500 mg per day. Though side effects were statistically significant in this small study group of 22 patients, only two became more agitated; one more confused, one experienced worsened EPS; and four required dosage reductions to reduce sedation.20

Of particular interest is the fact that physical aggression seems to respond more significantly than verbal aggression with divalproex. While side effects and drug interactions with both agents are serious concerns, they may prove very effective when other agents fail, and adding them to certain other regimens may be an appropriate option for enhancing efficacy.8,19 Side effects, precautions, and drug interactions are numerous, and the reader is referred to the literature for relevant information. Both agents have extensive involvement in cytochrome P450 enzyme systems, which can complicate other, diverse regimens and require careful patient selection in addition to selection criteria discussed here.12

Lithium has been used in some similar cases with largely anecdotal improvement seen in agitation in depressed patients; though improvement in hyperactivity, irritability, and pressured speech might be anticipated from other applications, evidence does not support these postulates. Clinical studies to evaluate lithium in this patient population have not been conducted.3

Antidepressants

True clinical depression is actually rare in AD or dementia patients, though the symptoms observed in disruptive behaviors that are seen with dementia can certainly overlap with those of depression. While other options may be considered first, antidepressants are often used when depression seems a significant factor in symptomatology. The selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors are one viable option, with sertraline and paroxetine leading this list. The longer half-life of fluoxetine is considered a liability in the elderly patient who may have impaired elimination. Compared to other drug classes considered in these applications, the SSRIs are relatively benign with respect to side effects and drug interactions with medications elderly patients are most likely to take.8

Trazodone is often used in this patient population as a short-term means of managing anxiety and insomnia. Low doses are appropriate (25 mg to 50 mg per day initially), with sedation usually lasting around 8 hours. Dizziness can be a concern with larger doses and when used for depression and anxiety during the day.8

Anxiolytics

There is some evidence that buspirone, with its low incidence of side effects, may have some application in managing anxiety and agitation in demented patients. Headache, dizziness, and nausea occur with relative infrequency, and overstimulation is possible. Beneficial effects begin gradually, with dosage adjustments over a period spanning 2 to 6 weeks, but addition of other antidepressants or anxiolytics can complicate the regimen with side effects and drug interactions.8

Though benzodiazepines are often used for anxiety in the elderly, and specifically in the elderly demented, they can cause their own problems with dependence and drug interactions. Alprazolam has been studied as an alternative to haloperidol in management of agitation with favorable results, showing that it produced benefits comparable to those of haloperidol without the liability of EPS and TD and with no detriments involving exacerbation of cognitive impairment or orthostasis.15

CONCLUSION

Alzheimers disease is the major cause of dementia -- impaired cognition -- in the elderly patient. Regardless of dementia’s cause, at some point during the progression of the primary disorder, disruptive behaviors become problematic enough to precipitate either institutionalization or treatment of caregivers for stress-related illness. Nonpharmacologic measures are appropriate in all cases.

Hard clinical evidence showing efficacy and safety for any medical intervention for disruptive behaviors is limited at best. But current evidence points to atypical antipsychotics as a promising alternative to the typical antipsychotic agents for management of disruptive behaviors. These agents provide more effective control with fewer side effects in the target population and fewer potential drug interactions with other medications likely to be required in elderly demented patients. Acetylcholinesterase inhibitors used primarily to delay cognitive symptoms may also prove valuable in this role, but probably only during the early stages of AD.

The anticonvulsants, most notably divalproex, show great promise in reducing the impact of disruptive behaviors, both alone and in conjunction with other agents, but their side effects and drug interactions may limit their useful application in the target population. Antidepressants, both SSRIs and trazodone, have proven beneficial in some cases where depression became a significant contributing factor to such behaviors, while anxiolytics, lithium, and even beta-blockers have been shown to be beneficial, though clinical evidence is lacking. Clearly, better clinical studies are required to provide reliable pharmacotherapeutic recommendations, while standardized and reliable means of assessing and quantifying the various disruptive behaviors must be devised in order to evaluate such trials.

Until better data become available, clinicians are guided to choose pharmacotherapeutic agents according to psychobehavioral metaphor and relevant side effect profile of the available agents, along with available clinical experience. In all cases, the patient’s quality of life and the effects of whatever long-term pharmacotherapy chosen should be primary considerations.

QUESTIONS

1. Noncognitive disruptive behaviors include which of the following?

a. dementia and nighttime restlessness

b. psychotic symptoms and physical aggression

c. disruptive vocalizations and dementia

d. dementia and verbal aggression

2. Which is the most common cause of dementia?

a. multi-infarct dementia

b. trauma or infection

c. Alzheimers disease

d. Pick’s disease

3. Which is the most significant risk factor for A1zheimer’s disease?

a. advancing age

b. cognitive decline

c. psychotic symptoms

d. disruptive behaviors

4. Wltich of these mental disorders could be confused with dementia?

a. psychosocial stress

b. attention deficit

c. age—related memory loss

d. sensory enhancement

5. Dementia can be defined as loss of memory and impairment of which of the following?

a. abstract thinking

b. mathematical reasoning

c. neurological orientation

d. cognitive observation

6. Which is the most common disruptive behavior among demented elderly patients?

a. delusions

b. hallucinations

c. agitation

d. physical aggression

7. Which two disruptive behaviors tend to be more common in moderate dementia than mild or severe forms?

a. agitation and verbal aggression

b. anxiety and physical aggression

c. hallucinations and anxiety

d. irritability and dysphoria

8. Disinhibition is seen in about what percentage of AD patients?

a. 50%

b. 40%

c. 50%

d. 60%

9. The additional functional iinpairment observed with disruptive behaviors is probably due to which of the following?

a. early institutionalization

b. medication

c. inadequate care

d. frequent fluctuations between frustration and impatience

10. Choose the best answer to complete this statement. Clinical studies comparing relative efficacy and

safety of the available atypical antipsychotic agents:

a. are difficult to interpret because of differences in rating scales

b. require a homogeneous subject group of elderly with the same severity and duration of dementia

c. are suspect because of nursing facility staff ineptitude

d. have not been done extensively in elderly demented patients

11. Which of the following is one of the most significant factors in optimizing care of patients with impaired cognitive function?

a. educating caregivers

b. avoiding institutionalization

c. recognizing sundowning

d. avoiding irritability

12. Pharmacotherapy for disturbing behaviors is aiined at which of the following goals?

a. periodic reassessment

b. symptom control

c. PRN use

d. chemical restraint when appropriate

13. Depression in the demented elderly patient is generally most appropriately treated with which of the following?

a. typical antipsychotics

b. atypical antipsychotics

c. tricyclic antidepressants

d. selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors

14. Choose the best answer to complete this statement. Cognitive decline in AD:

a. can be prevented by cholinomimetic agents

b. and disruptive behaviors are due to identical pathologies

c. can be delayed by SSRIs

d. is attributed largely to cholinergic deficiency

15. Which of the following agents is most likely to impair liver function?

a. tacrine

b. donepezil

c. rivastigmine

d. quetiapine

16. Which of the following agents is least likely to be involved in drug interactions involving the cytochrome P450 enzyme systems?

a. tacrine

b. rivastigmine

c. carbamazepine

d. divalproex

17. Which of the following side effects is least likely with typical antipsychotics?

a. insomnia

b. orthostatic hypotension

c. extrapyramidal symptoms

d. tardive dyskinesia

18. Which of these agents is least likely to cause extrapyramidal side effects (EPS)?

a. haloperidol

b. risperidone

c. quetiapine

d. olanzapine

19. Which dose of olanzapine has shown the best long-term results thus far in reducing agitation with

prominent psychotic symptoms in AD patients?

a. 20 mg

b. 2.5 mg

c. 15 mg

d. 10 mg

20. Which of the following disruptive symptoms is most likely to be improved by divalproex?

a. physical aggression

b. verbal aggression

c. wandering

d. sundowning